Monthly Archives:

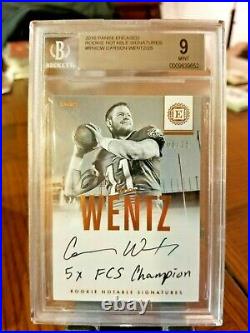

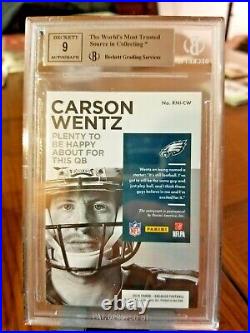

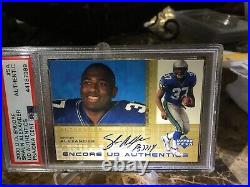

CARSON WENTZ /25 BGS 9 ROOKIE Notable AUTO Inscribed RC SP 2016 PANINI ENCASED

Nice Condition, Clean and. From a Pet and Smoke Free Home! Please use the photos to judge item condition for yourself. All items may have some creases, marks, scratches, smears and/or and dust on them from. We strive to be reasonable in the event of a disagreement and ask that buyers afford us the same level of fairness. This item is in the category “Sports Mem, Cards & Fan Shop\Sports Trading Cards\Trading Card Singles”. The seller is “collectorsmantle” and is located in this country: US. This item can be shipped to United States, Canada, United Kingdom, Denmark, Romania, Slovakia, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Finland, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Estonia, Australia, Greece, Portugal, Cyprus, Slovenia, Japan, China, Sweden, Korea, South, Indonesia, Taiwan, South Africa, Thailand, Belgium, France, Hong Kong, Ireland, Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Italy, Germany, Austria, Bahamas, Israel, Mexico, New Zealand, Philippines, Singapore, Switzerland, Norway, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Kuwait, Bahrain, Croatia, Republic of, Malaysia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Panama, Trinidad and Tobago, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Jamaica, Antigua and Barbuda, Aruba, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Saint Kitts-Nevis, Saint Lucia, Montserrat, Turks and Caicos Islands, Barbados, Bangladesh, Bermuda, Brunei Darussalam, Bolivia, Ecuador, Egypt, French Guiana, Guernsey, Gibraltar, Guadeloupe, Iceland, Jersey, Jordan, Cambodia, Cayman Islands, Liechtenstein, Sri Lanka, Luxembourg, Monaco, Macau, Martinique, Maldives, Nicaragua, Oman, Peru, Pakistan, Paraguay, Reunion, Vietnam, Uruguay.

- Set: 2016 Panini Encased

- Card Number: RNI-CW

- Season: 2016

- Graded: Yes

- Player/Athlete: Carson Wentz

- Grade: 9

- Type: Sports Trading Card

- Features: Rookie

- Manufacturer: Panini

- Professional Grader: Beckett Grading Services (BGS)

- Sport: Football

- Original/Licensed Reprint: ORIGINAL

- Team: Philadelphia Eagles

- League: National Football League (NFL)

- Autographed: Yes

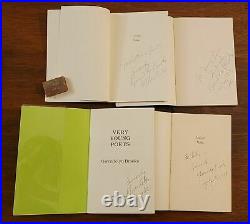

Argentina Author Legend Signed Ocampo Original Famous Vintage Autograph